Code

Julius Ndung’u

June 5, 2024

In the ever-evolving field of agriculture, the quest for higher yields,improved crop quality, and sustainable practices has been the catalyst for more Research. At the heart of these advancements lies a fundamental yet often overlooked tool: experimental design. Experimental designs in agriculture serve as the blueprint for systematic investigation,enabling researchers to test hypotheses, compare treatments, and draw reliable conclusions. Whether it’s optimizing fertilizer usage,developing pest-resistant crop varieties, or enhancing soil health,carefully crafted experimental designs are essential for translating scientific inquiry into practical solutions. This blog delves into the significance of experimental designs in agriculture, exploring how they drive innovation and shape the future of farming. Join me as I uncover the methodologies that help transform agricultural research from theoretical concepts into tangible benefits for farmers and consumers alike.

Precision and Accuracy Agricultural experiments often involve studying the effects of various factors such as soil types, fertilizers, crop varieties and environmental conditions on crop yield, quality and other agronomic traits. By employing well-designed experimental designs, researchers can ensure that the results obtained are precise and accurate, reducing variability and enabling reliable comparisons betweentreatments.

Efficiency Effective experimental designs maximize the use of available resources including land, labor and materials. By carefully planning the layout of experimental plots or treatment groups, researchers can achieve statistically efficient designs that yield reliable results withminimal waste.

Control of Confounding Factors Agricultural systems are complex, with multiple factors influencing crop growth and performance. Experimental designs allow researchers to control for potential confounding factors by randomly assigning treatments to experimental units or by employing blocking and stratification techniques. This helps isolate the effects of specific treatments and reduces bias in the results.

Inference and Generalization Well-designed experiments provide a basis for making valid inferences and generalizations about the effects of treatments on crop performance. By ensuring the internal validity of the experiment through proper design and analysis, researchers can confidently extrapolate their findings to broader agricultural contexts,guiding farm management practices, policy decisions and future research directions.

Adaptability to Field Conditions Agricultural experiments often take place in field settings, where environmental variability and logistical constraints pose challenges to data collection. Experimental designs tailored to field conditions, such as randomized complete block designs or split-plot designs, allow researchers to account for spatial variability and field heterogeneity, enhancing the relevance and applicability of the results to real-world agricultural scenarios.

Statistical Analysis and Interpretation Agricultural research generates large volumes of data, requiring sophisticated statistical methods for analysis and interpretation. Properly designed experiments provide the necessary structure and replication for applying robust statistical techniques, such as analysis of variance (ANOVA), regression analysis and mixed-model approaches, to extract meaningful insights from the data.

Resource Allocation and Risk Management Agricultural production involves inherent risks related to weather variability, pest and disease outbreaks, market fluctuations and other factors. Experimental designs help farmers and agricultural stakeholders make informed decisions about resource allocation, risk management strategies, and technology adoption by providing evidence-based insights into the performance of different practices, inputs and technologies under varying conditions.

Optimization of Inputs By conducting experiments to evaluate the effects of different inputs such as fertilizers, irrigation methodsand crop varieties on yield, quality, and resource use efficiency, farmers can optimize their use of inputs to maximize productivity while minimizing costs and environmental impact.

Adaptation to Climate Change Experimental designs allow researchers to assess the resilience of crops and farming systems to climate change-induced stressors such as drought, heat, and pests. By identifying resilient crop varieties and management practices through experimentation, farmers can adapt their farming systems to changing climatic conditions and mitigate the negative impacts of climate change on agricultural productivity.

Enhancement of Sustainability Experimentation plays a crucial role in developing and promoting sustainable farming practices that conserve soil, water and biodiversity while maintaining or improving yields. By testing innovative approaches such as conservation agriculture, agroforestry and organic farming through well-designed experiments, farmers can transition towards more sustainable production systems that enhance long-term productivity and environmental health.

Integration of Technology Experimental designs facilitate the evaluation of emerging technologies such as precision agriculture,remote sensing, and digital farming tools in real-world farming contexts. By conducting on-farm trials and field experiments,researchers and farmers can assess the efficacy and economic viability of new technologies and determine their potential to enhance efficiency,productivity and profitability in farming operations.

Empowerment of Farmer Decision-Making Through participatory research approaches and farmer-led experimentation, farmers become active participants in the innovation process, contributing their knowledge, experiences and preferences to the design and implementation of agricultural experiments. This participatory approach not only generates locally relevant solutions but also empowers farmers to make informed decisions about adopting new practices and technologies that best suit their needs and circumstances.

Resilience Building: Experimental designs enable the testing of diverse cropping systems, crop rotations, and agroecological principles to enhance the resilience of farming systems to biotic and abiotic stresses. By promoting biodiversity, soil health, and ecosystem services through experimentation, farmers can build resilient farming systems that are better equipped to withstand shocks and disturbances while maintaining productivity and profitability over the long term.

Knowledge Sharing and Collaboration Experimental research fosters collaboration and knowledge sharing among researchers, extension agents,farmers and other stakeholders within the agricultural community. By disseminating research findings, best practices, and lessons learned from experiments through extension programs, farmer field schools, and digital platforms, innovative solutions and technologies can be scaled up and adopted more widely, driving collective learning and continuous improvement in farming practices.

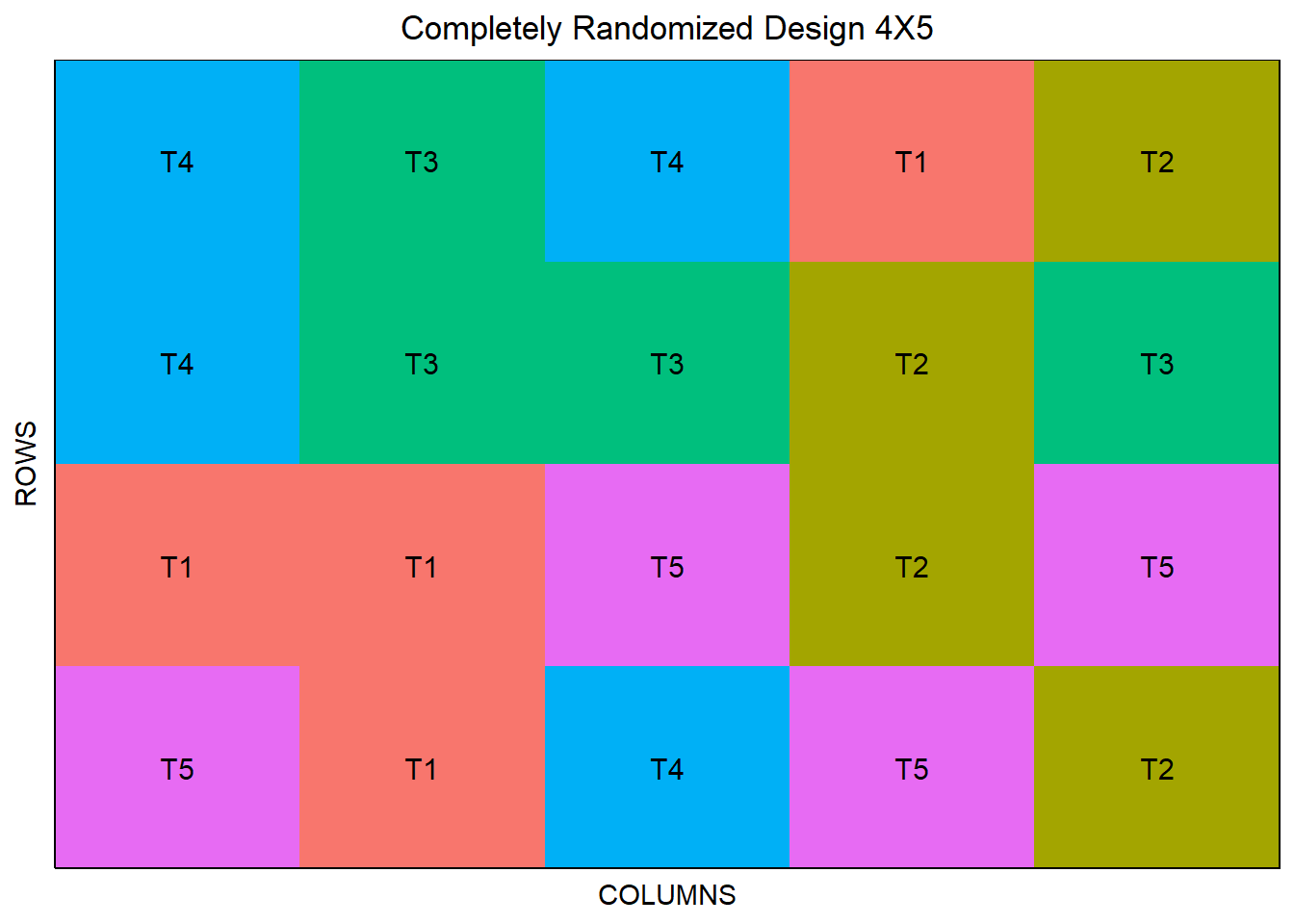

Layout The whole field is divided into plots of similar shape and size. The number of plots is equal to the product of treatments and replications.These plots are then serially numbered.

Replications There is no restriction on the number of replications in this design.The number of replications can vary from treatment to treatment.Normally, the number of replications for different treatments should be equal to get the estimates of treatment effects with same precision. The number of replication depends on the availability of experimental material and level of precision required.

Randomization The randomization is done treatment wise with the help of random table.First random numbers equal to the number of plots are taken from the random table. From these random numbers each treatment is assigned numbers as per number of replications. Then random numbers of each treatment are allotted to the plots bearing the serial number similar to the random number.

Suitable for homogeneous fields where environmental conditions are uniformly spread.

Simplicity: Easy to set up and analyze.

Flexibility:Suitable for any number of treatments.

Cost-effective: Requires fewer resources in terms of time and labor.

| Source of Variation | Degrees of Freedom(DF) | Sum of squares(SS) | Mean Sum of Squares(MSS) | F-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | t-1 | SST | MST | MST/MSE |

| Error | N-t | SSE | MSE | |

| Total | N-1 | SST+SSE |

First the experimental field is divided into homogeneous groups equal to the number of replications. These homogeneous groups are known as blocks. Then each block is further divided into plots of similar shape and size equal to the number of treatments.

There is no restriction on the number of replications. However, all the treatments should have equal number of replications.

The treatments are allotted to the plots in each block by a random process. Separate randomization is used in each block.

Used when there is a need to control for variability in one direction, such as fertility gradients.

Control of Variability: Blocks account for variations,improving the precision of treatment comparisons.

Efficient: Reduces experimental error.

| Source of Variation | Degrees of Freedom(DF) | Sum of squares(SS) | Mean Sum of Squares(MSS) | F-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | t-1 | SST | MST | MST/MSE |

| Blocks | b-1 | SSB | MSB | MSB/MSE |

| Error | (t-1)(b-1) | SSE | MSE | |

| Total | tb-1 | SST+SSB+SSE |

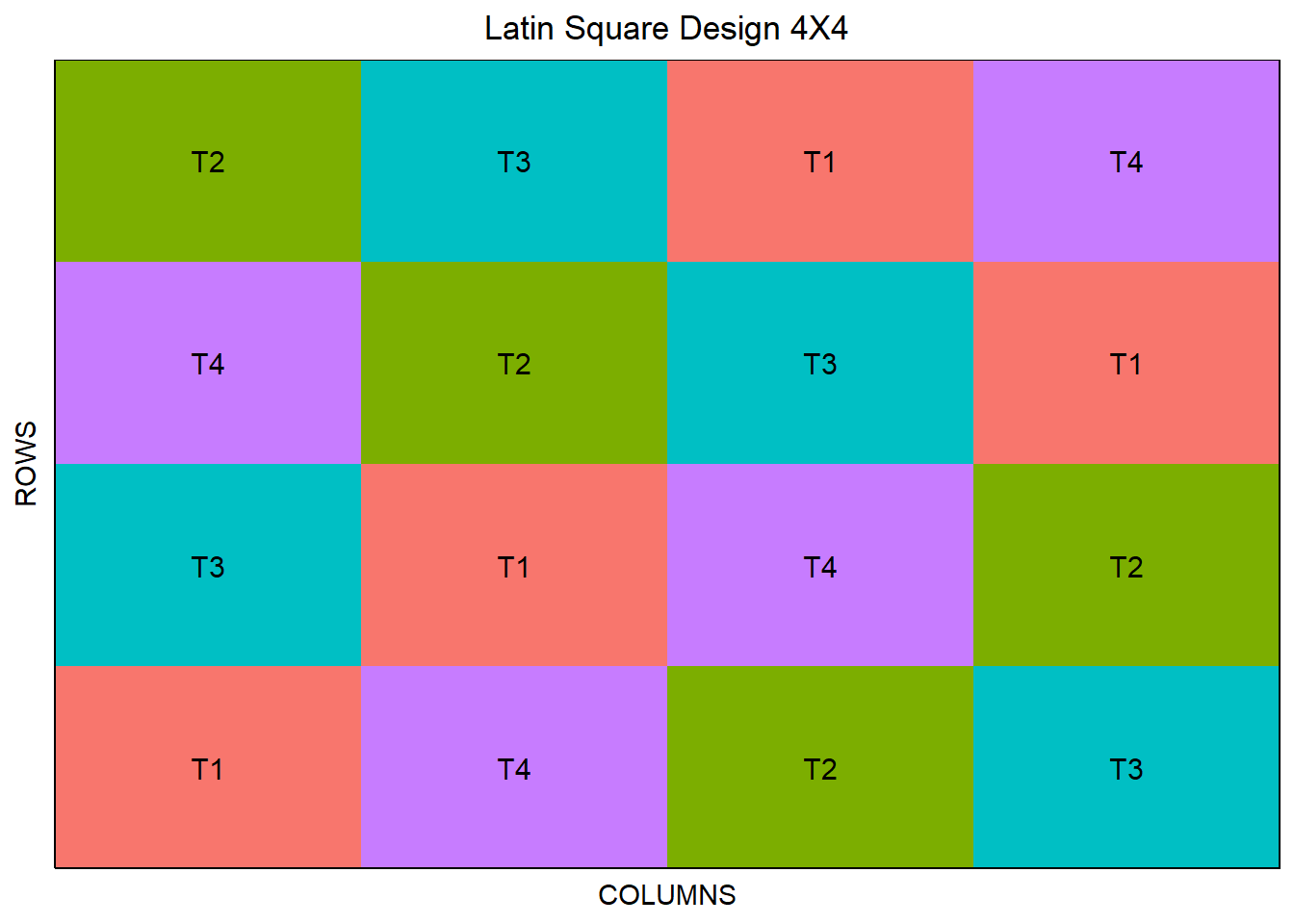

The experimental design which simultaneously controls the fertility variation in two directions is called Latin square design (LSD). In other words, Latin square designs are adopted for eliminating the variation of two factors which are generally called rows and columns.

Layout Treatments are arranged in a square grid where each treatment appears exactly once in each row and each column.

Application: Useful when controlling for two sources of variability, such as row and column effects.

Effectively controls variability in two directions.

Efficient Use of Resources: Reduces the number of experimental units needed.

Complexity: More complex to implement and analyze.

Limited Treatments: Only practical for a limited number of treatments.

l <- latin_square(t = 4,

reps = 1,

plotNumber = 101,

seed = 1980)

plot(l)

| Source of Variation | Degrees of Freedom(DF) | Sum of squares(SS) | Mean Sum of Squares(MSS) | F-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | t-1 | SST | MST | MST/MSE |

| Rows | t-1 | SSR | MSR | MSR/MSE |

| Columns | t-1 | SSC | MSC | MSC/MSE |

| Error | (t-1)(t-2) | SSE | MSE | |

| Total | (t^2)-1 | SST+SSR+SSC+SSE |

t = Number of treatments (also the number of rows and columns)

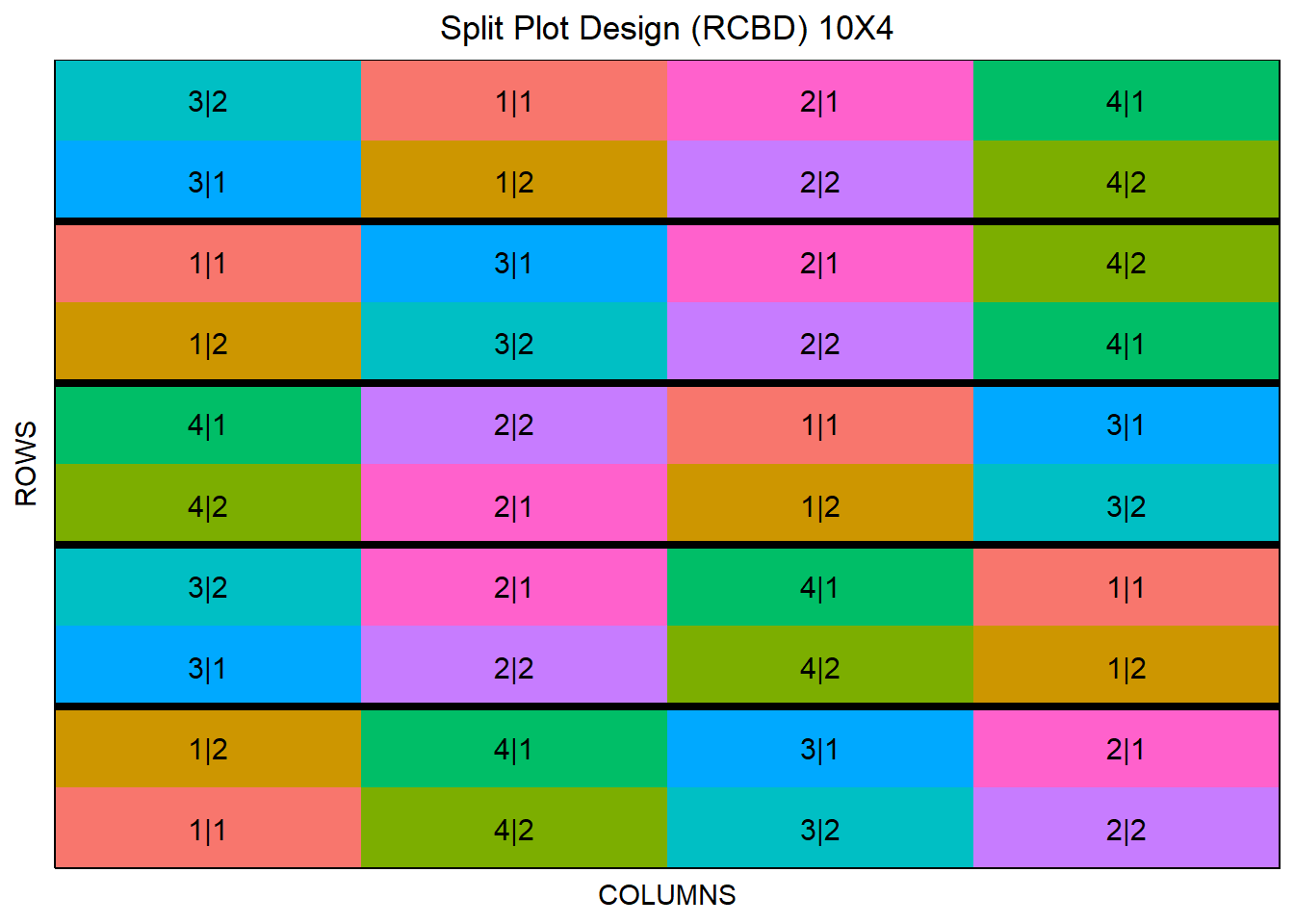

The experimental design in which experimental plots are split or divided into main plots, subplots and ultimate-plots is called split plot design (SPD). In this design several factors are studied simultaneously with different levels of precision. The factors are such that some of them require larger plots like irrigation, depth of ploughing and sowing dates, and others require smaller plots.

Main plots are divided into subplots, with one factor assigned to main plots and another factor to subplots.

Useful when dealing with factors that are hard to change (main plots) and factors that are easy to change (subplots).

Flexibility: Allows testing of interactions between main plot and subplot factors.

Practical: Reduces costs when one factor requires large plots or extensive management.

Complexity: More complex statistical analysis required. Error Structure

Different error terms for main plot and subplot factors.

with 4 whole plots, 2 sub plots per whole plot, and 4 reps in an RCBD arrangement. This in for a single location.

# Example 1: Generates a split plot design SPD

SPDExample1 <- split_plot(wp = 4, sp = 2, reps = 5, l = 1,

plotNumber = 101,

seed = 14,

type = 2,

locationNames = "FARGO")

plot(SPDExample1)

| Source of Variation | Degrees of Freedom(DF) | Sum of squares(SS) | Mean Sum of Squares(MSS) | F-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main plot(A) | a-1 | SSA | MSA | MSA/MSE1 |

| subplot(within main plots) Error (Whole plot) | a(b-1) | SSE1 | MSE1 | |

| Subplots(B) | b-1 | SSB | MSB | MSB/MSE2 |

| Interaction(A*B) | (a-1)(b-1) | SSAB | MSAB | |

| Subplots Errors | ab(r-1) | SSE2 | MSE2 | |

| Totals | abr-1 | SST |

a= Number of main plot treatments

b= Number of subplot treatments

r= Number of replicates